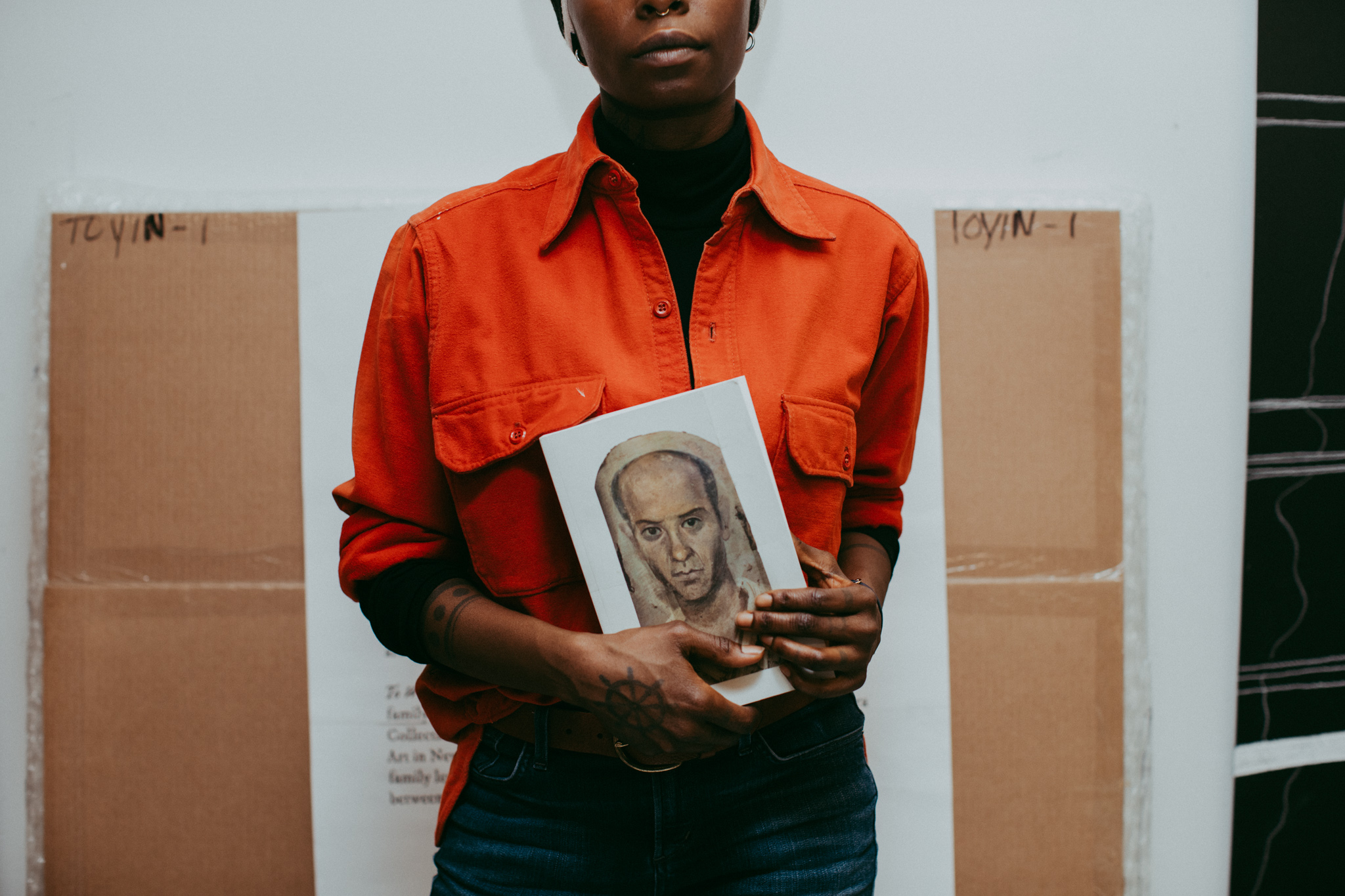

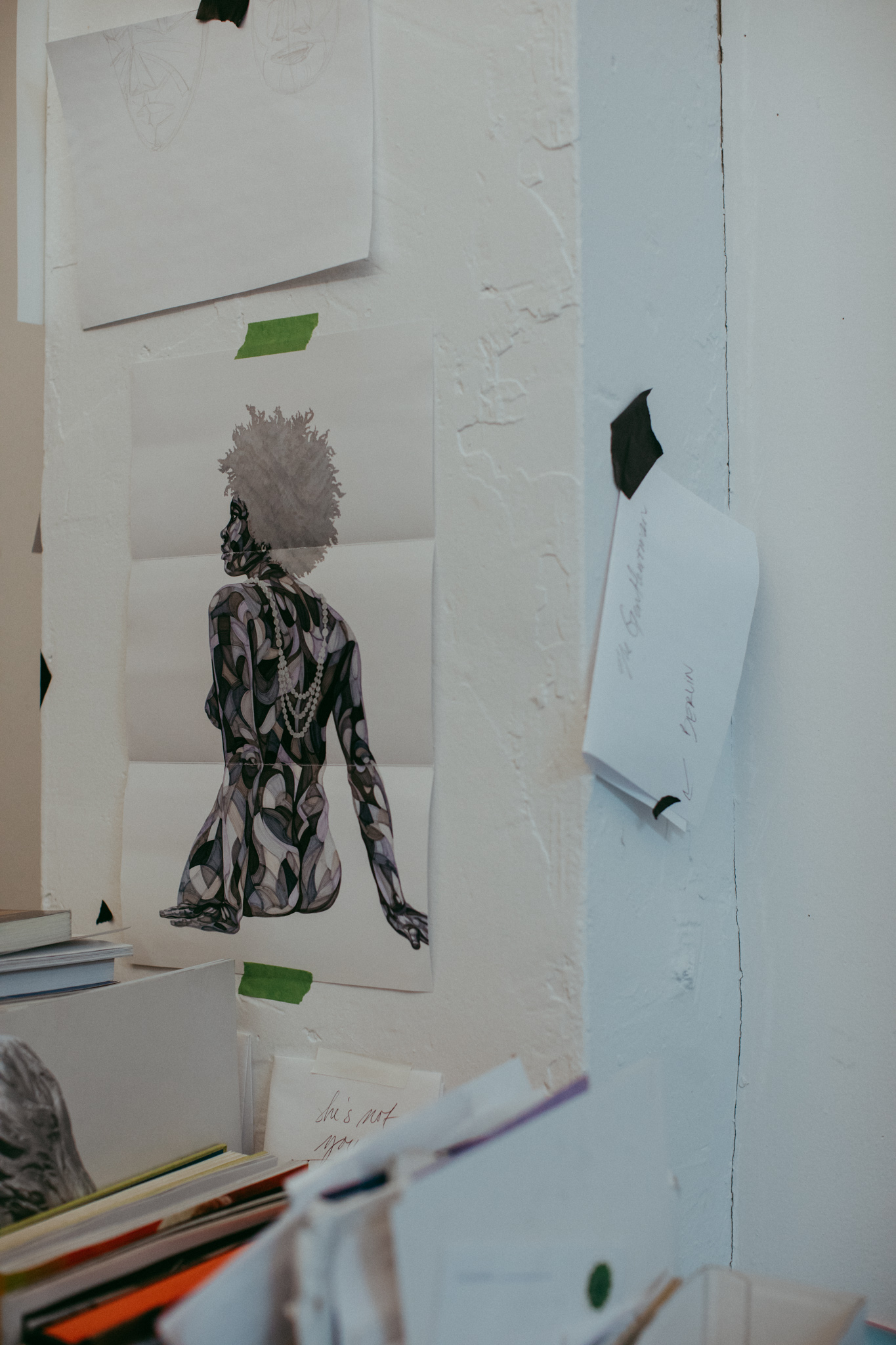

Toyin Ojih Odutola

Toyin Ojih Odutola is an emerging artist living and working in New York City. To Wander Determined is her first New York solo show in at The Whitney, currently on view until February 25th. Toyin is a master at using mark making with elementary tools to create her nuanced drawings that, upon first glance, read as complex and beautifully designed figure paintings. The fact that they are drawings is a point worth noting. Humble materials are spun into gold in Toyin’s hands. GAL discovers how she creates narrative within her specific visual language, building new structures and narratives around the way we see and think about art. Join us as we discuss everything from process to prose.

Photography by Sylvie Rosokoff

Girls at Library: How does it feel to have a solo show at The Whitney?

Toyin Ojih Odutola: Honestly, I haven't processed it. I had to go back to the studio right after the show opened, because I had to prepare for another solo exhibition. So, while everyone told me, “This is a nice time for you to finally relax and let it all in.” I couldn't tell them I had a book coming out, and that I’m a Barnard fellow now—with all that it entails—in addition to creating these new works. I was consumed by the work, and so I couldn't really think about the show. A blessing and a curse. At the same time, the responses have been incredibly overwhelming, and really heartwarming. You don't expect this kind of thing. You spend time working alone for months, and all you're focused on is in the making. You have no idea what that work will become once it leaves your studio.

GAL: Does audience response matter to you?

TOO: My hope is always for at least one person to find a connection to any of the pieces in the show. My friend from Alabama visited recently. One of the pieces in the exhibition was inspired by her son, and so, she came here to see it. She cried, and it was a really emotional moment. It just hit me how you put a lot of yourself into your work, and it can be rather personal, so you want to preserve and protect that. At the same time, you don't want to discount what other people feel and their connection to that work and the beauty in their connection. That’s been my takeaway from the show: people are seeing it and have their own personal connection to it, which is really incredible and quite inspiring, actually.

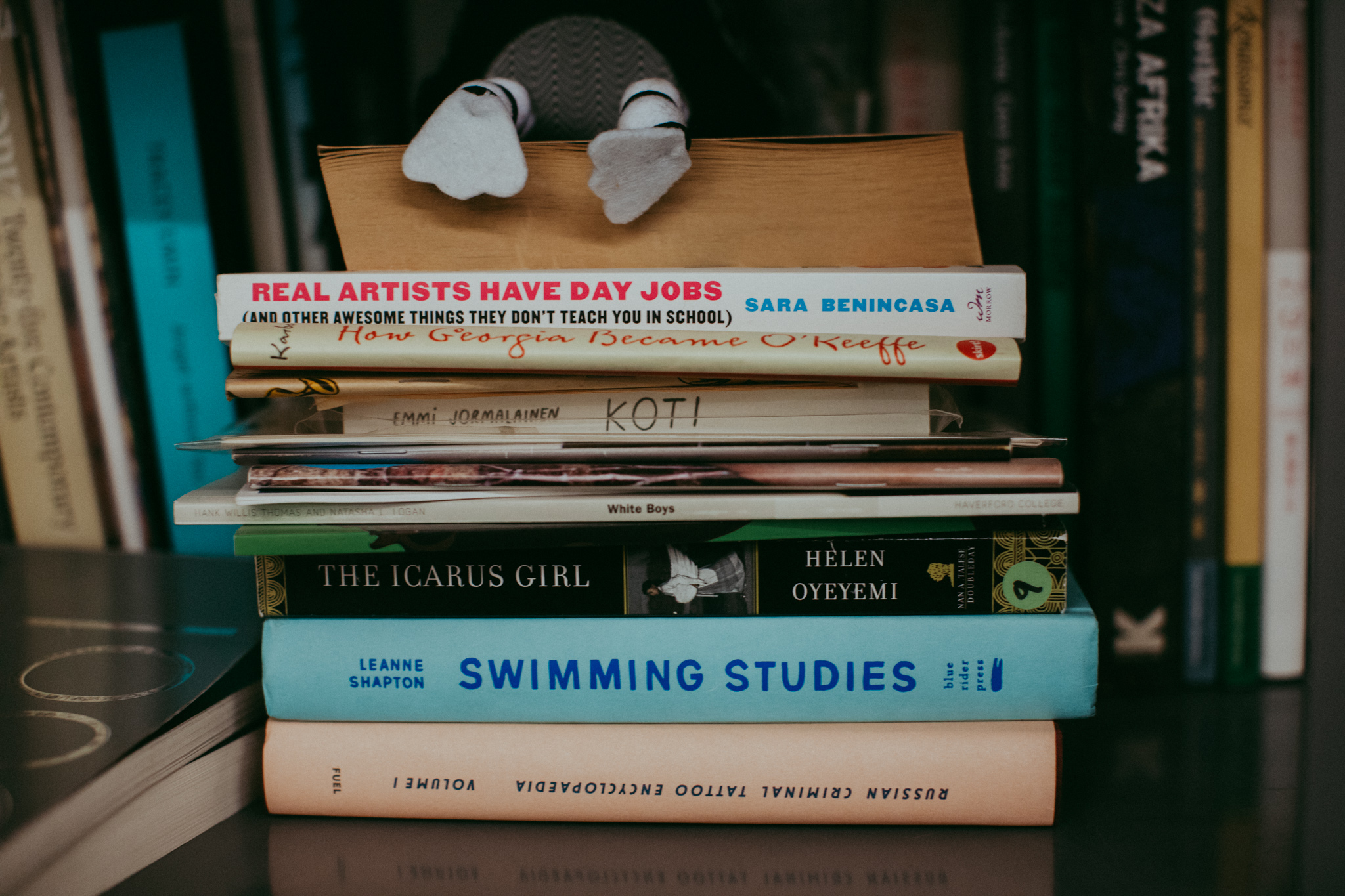

GAL: What are you reading right now?

TOO: I'm doing a lot of research reading so I'm all over the place. I'm re-reading Toni Morrison’s Sula. And I'm also reading her latest book The Origin of Others. I'm one of those people who reads multiple books at a time, I can’t help it. Never Let Me Go, by Kazuo Ishiguro. I'm reading a lot of John Berger, but he's a constant. He is just brilliant.

GAL: What's the power of story? Have any fictional narratives inspired you or changed your life?

TOO: Yes, there’s a lot of power in a story. When I started my career, I used my own image a lot. Not out of some kind of autobiographical inclination, it really had little or nothing to do with me. When you use someone else’s image, when you use someone's face, there's a capital to that, and you're taking that capital when you choose to use it. How and what you choose to use it is very important. So, I wouldn't draw other people as much. I’d usually draw myself or ask my brothers if I could draw them.

Because of this, the read was often about autobiographical indications or something to do with black femininity and womanhood as a whole. It frustrated me, because it completely disregarded my capacity for an imagination. There was no possibility seen or room for lending my face to a work which was separate from me as a person.

I think a lot of that has to do with the style I employ. It's very layered and very black, but then, I realized maybe the reason people were reading the work in that way was because it lacked narrative.

GAL: How so?

TOO: You were only seeing the figure by itself, whereas I was seeing a world within that figure, which could be interpreted and read in a myriad of ways. I didn't think context was needed when there was so much language laid onto the skin, on the very body. You have to learn to read that. You may not be familiar with that language, but that language is important nonetheless.

I wasn't necessarily trying to create a type of work which was obfuscating, I simply wanted to share a language of the skin beyond metaphor. So, I decided to move away from that decontextualization by removing myself out of the conversation, which I felt was distracting and didn't help the work. The beauty of injecting the fictive is how it can be a part of you, but it’s own separate entity. As an artist of color, it’s a luxury, because your otherness is no longer central in the conversation. It's something else in the story. It’s a starting point.

GAL: So people can get lost in the story itself.

TOO: Yes, and it doesn't become this dead-end conversation. No one wants to come into a work, thinking, “Oh, yes. Please remind me of the social structures that decide my life and make it very difficult to live” and have that be the final read. Whereas, if you come in and you see a story, there's so much more potential for a rich experience. Blackness can be a catalyst. It doesn't have to be a finite point or a dead end. Also, I’m not here to talk about pain.

Incorporating the fictive is what allowed me to expand not only the definition of blackness, but to expand what blackness can contain, what blackness can reveal, and where it can go. It's no longer flattened nor monolithic. It's not stuck in some loop that is only binary to whiteness. No one wants to have that cyclical conversation anymore, it limits so much of what the work can be. And if all you see of the work is that, it's indicative of how you see the world, how you see people.

To Wander Determined is also a personal tip of the hat to my 14 to 16-year-old teen self, who was obsessed with Jane Eyre and Pride and Prejudice. Reading those stories, there was always a moment when I thought, “God, I wish I could create something like this. I wish I could be a part of this kind of story without my blackness getting in the way of that.” Can I be Jane Eyre without being a black Jane Eyre? I don't know.

“Can I be Jane Eyre without being a black Jane Eyre?”

GAL: Can you be an artist without being a female artist?

TOO: Or a black woman artist? There’s power in the specificity of claiming those labels and standing firm in them, but it can become a veil or an obstruction, which clouds people’s judgement when they don’t have the tools or the patience to consider that specificity properly. And all of that can mess with you in the studio. When you inject story, it's so freeing. At least for me in the working and presentation of the work, because then I can really put things in which aren't indicative of anything but my own imagination or fancy. When you tell people from the start that the exhibition they are entering is a story, that veil is removed and they can walk through the works and see them without me being in the way.

GAL: Do you compose your figures from your imagination, or do you use source imagery?

TOO: I use both.

GAL: How so?

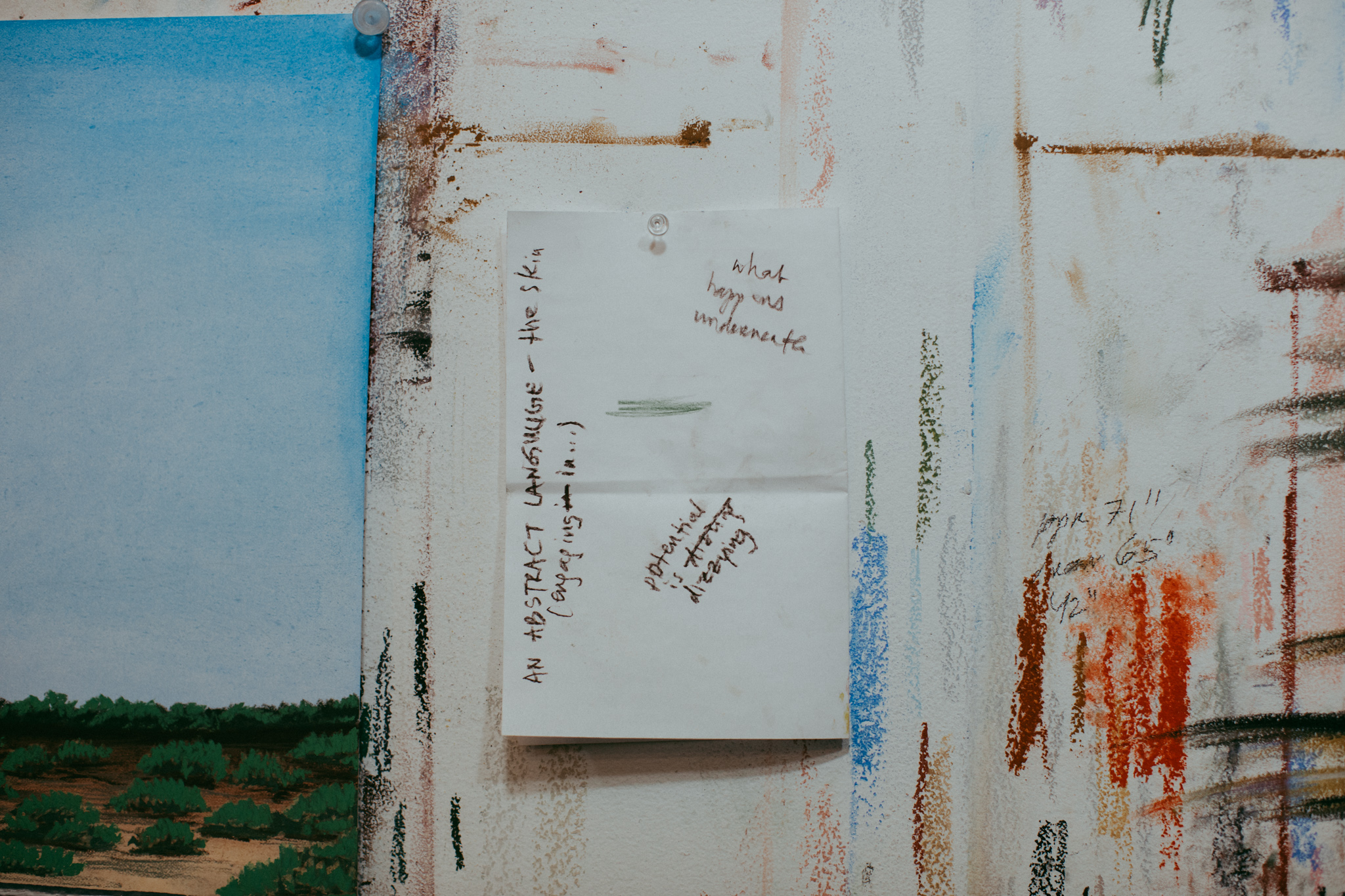

TOO: I do a lot of thumbnail sketches for each drawing I tackle. If I have an idea, I’ll do about five to 10 sketches playing with that idea. Compositional elements, editing, mapping out the various eventualities within the picture plane. I’ll ask myself, “How will this figure be arranged in the overall narrative? What am I thinking about in terms of the story? What clues should I add?” Once I begin to tackle the drawing itself, I collage together a variety of sources, from photographs I have taken to researched images, including my thumbnails. Using external sources to create a drawing is instructive, for it frees me up from my own expectations about the work. Those initial thumbnails are just guides. I don't want to be beholden to my own expectations or ideas about what I think the picture should be.

“What I’ve always been attracted to in visual art is when you can actually see the hand of the artist, when you see that slight idiosyncratic mark. if you want to get any sort of autobiography about the artist, just read the mark itself.”

GAL: Does it evolve through the process?

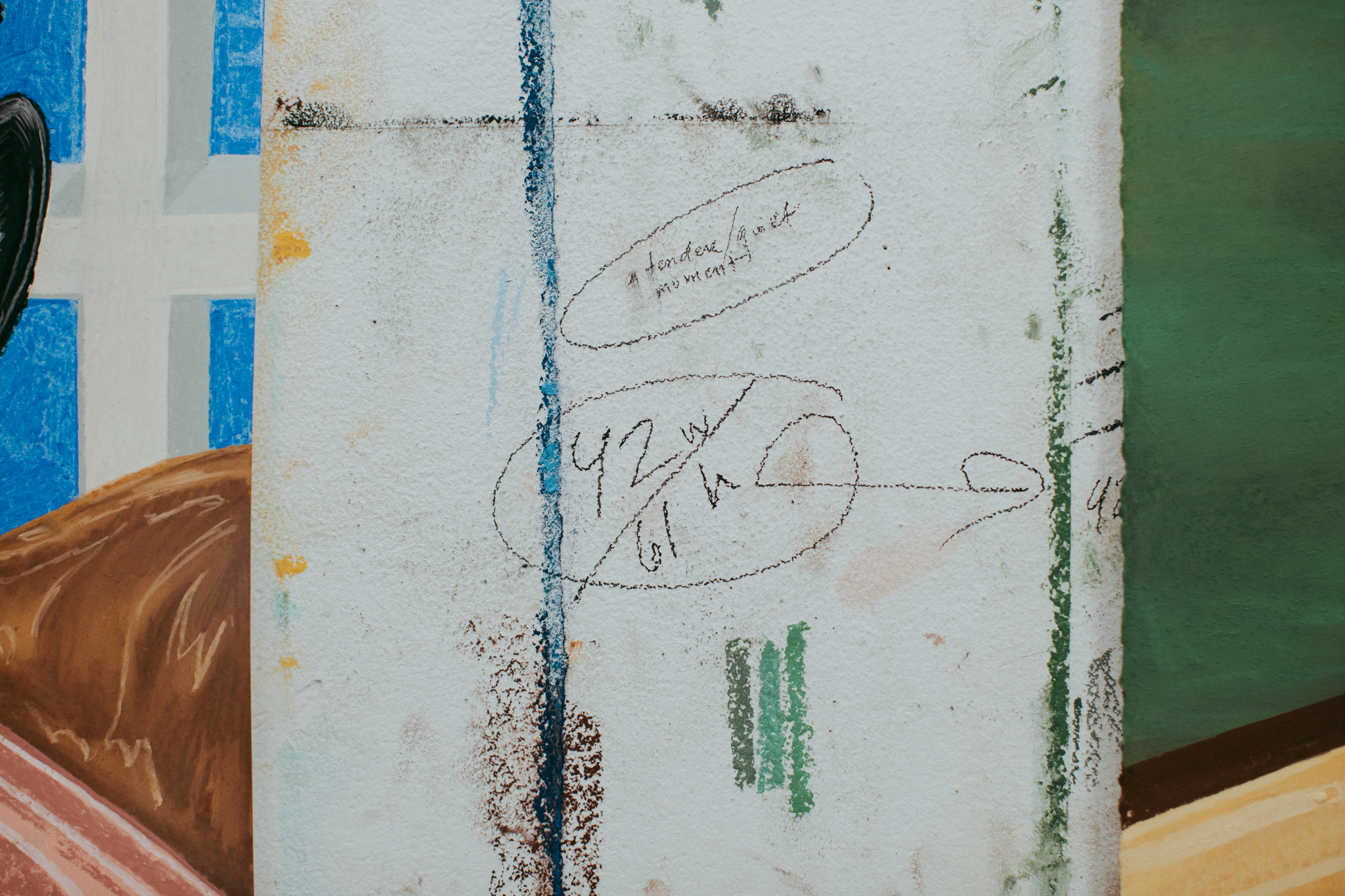

TOO: Yes. Once the final sketch is down, I start tackling it with charcoal, pastel, and pencil. I used to be very particular about how pictures should come out, but now I love when failure happens. When you can see the limitations of my hand revealed in the line work. For example, there are certain drawings in the show with slightly wobbly lines, and I love that. What I've always been attracted to in visual art is when you can see the hand of the artist, when you see that slight, idiosyncratic mark. If you want to get close to any sort of autobiography about an artist, just read the mark itself, the choices made there. Sometimes, the details don’t make any sense, but if you put each element together, that's a story in itself. That’s how I started with the monochromatic, early drawings—thinking about the story within the marks and the amalgam of marks—but I expanded the method with these new, more narrative driven works.

GAL: Why do you use drawing in dry medium over maybe more “obvious” or “traditional” wet media like oil painting? Your drawings read as paintings to me. Is there a reason?

TOO: Absolutely.

GAL: Enlighten us.

TOO: It’s involved in the overall conceit of the show. The viewer enters the space thinking they are seeing a wall of paintings, which belong to an old, moneyed family. All the works included in the exhibition were supposedly chosen from some rarified collection. The presumption being, any grand family estate collection would traditionally have paintings—large-scale paintings and genre paintings. The fact that the viewer realizes,

upon close inspection, that each work is created with dry media, and not only that, they're drawn and not painted, it makes one question presumptions not only about wealth, but about how objects are perceived, how objects exist in the world, and how they're used as tools. I've always been a drawer. I stand by that. I will fight to the death for it, because to me there's an immediacy to drawing, a directness.

GAL: There’s a deep, inherent closeness to drawings. You started with ballpoint pens, right?

TOO: I still work with ballpoint pen ink. When I started, a lot of my professors—especially in graduate school—were very perplexed by this. Questions like, “Why are you using a writing tool you can get at a doctor's office?” “What does this rudimentary, ubiquitous tool have anything to do with art and art making?” And I thought, “it has everything to do with art-making,” because if you look at these figures I’m creating, you can see how they're rendered so meticulously, so carefully with this rudimentary, ubiquitous tool. That this tool, like the assumption of so many other things and people, can contain all of this, can express all of this—is the point of art-making at its core.

GAL: The juxtaposition of that is so beautiful.

TOO: The notion that because the drawings in TWD are large, layered and complex, they must be painting, can be applied to so many other aspects—from constructs to the quotidian. It’s all about our perceptions and how expectation and presumption gets in the way of actually seeing the world in front of you. And how drawings can be just as layered, just as complex, and yet, you feel the immediacy more, you see the mistakes more.

GAL: Yes, the artist’s hand is much closer to the paper. It’s laid bare.

TOO: Not to say that paintings don't have that, but when you know someone's hand is working with a tool that's very direct, it has a different feel, a different read—at least for me in the making. It affects how the drawings are planned. I know I'm working with a tool which can’t hide anything.

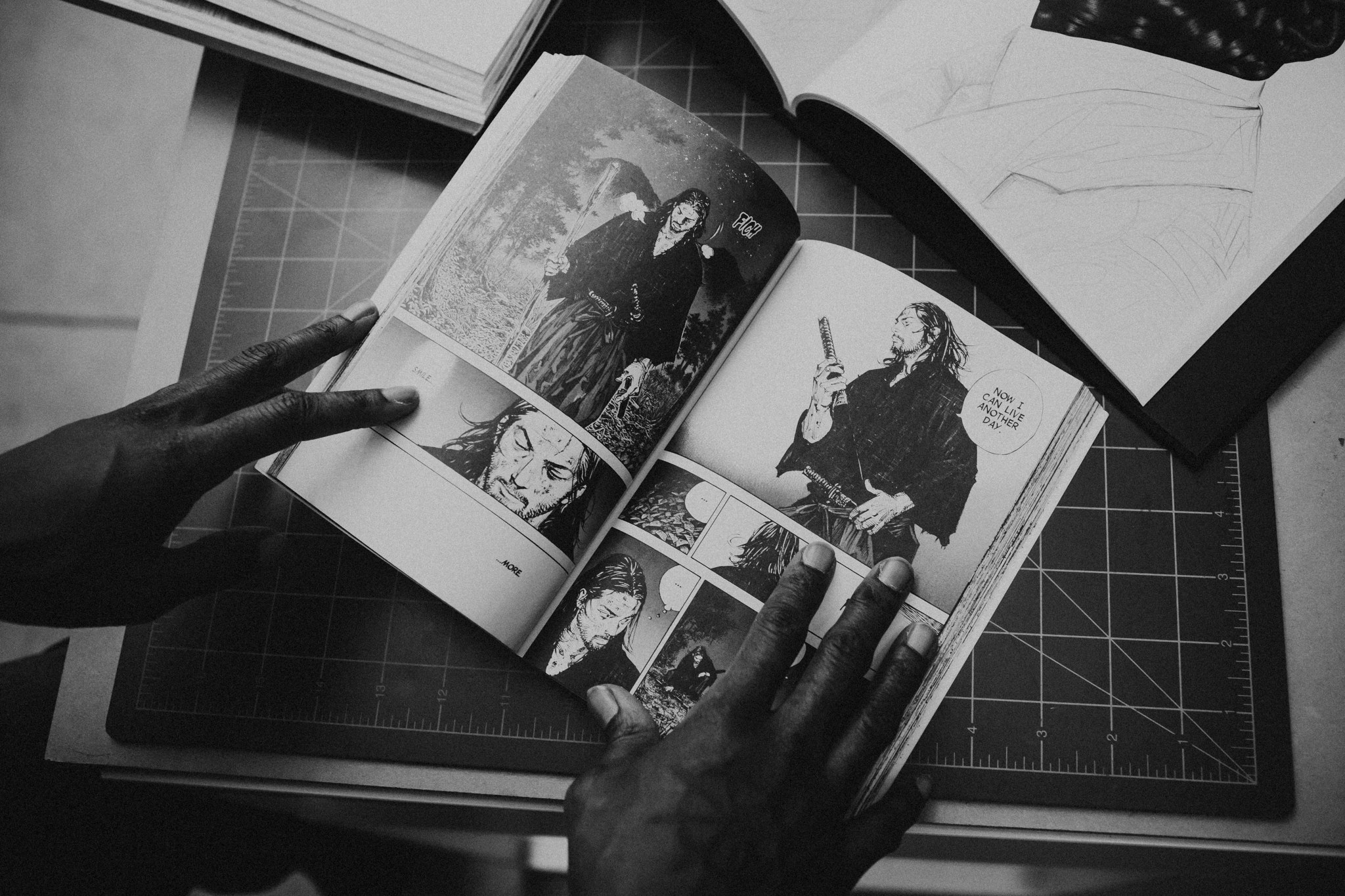

GAL: You grew up learning English through graphic novels and cartoons.

TOO: Yeah, partially. I didn't speak English very well when I was young and my mom, fortuitous in her thinking, took us to see Disney movies, as if, “Okay, well, Disney is a big thing. Let's take the kids to these movies so they can learn.” We knew very little about the subtle colloquialisms and cultural innuendos when we got here, and I was struggling to communicate in school—and all the rest of it. So, she would take us whenever she could, as often as she could, to educate us.

I remember seeing Aladdin in the theater and being completely blown away, and leaving the cinema amazed. My mother dropped the bomb: “You know, people drew that.” And my five or six year old mind was like… [explosion sound]. I needed to know more, I needed to understand how.

And so, she would get me these little coloring books of the film characters, so I could see the line work, and I just became obsessed. I think, too, with comic books, watching Japanese anime, as well as Disney movies, combined, I was educated on how to read the visual. I wasn't really big on text and I wasterrible at math. So, the visual became a means of understanding the world in a way I hadn’t before. It was

indispensable for communicating. I think, a lot of people don't understand how powerful that is in the world we live in—especially with the proliferation of advertising and the constant influx of images—to read an image the way you might read a letter or a novella. There's so much packed into an image that has its own rules and its own language—and it’s a fascinating world.

I didn't think I would be someone who could create that or be a part of that culture. I loved looking at an image, searching the pictures to discover the layers of meaning, a whole world of a story there, and reveling in that.

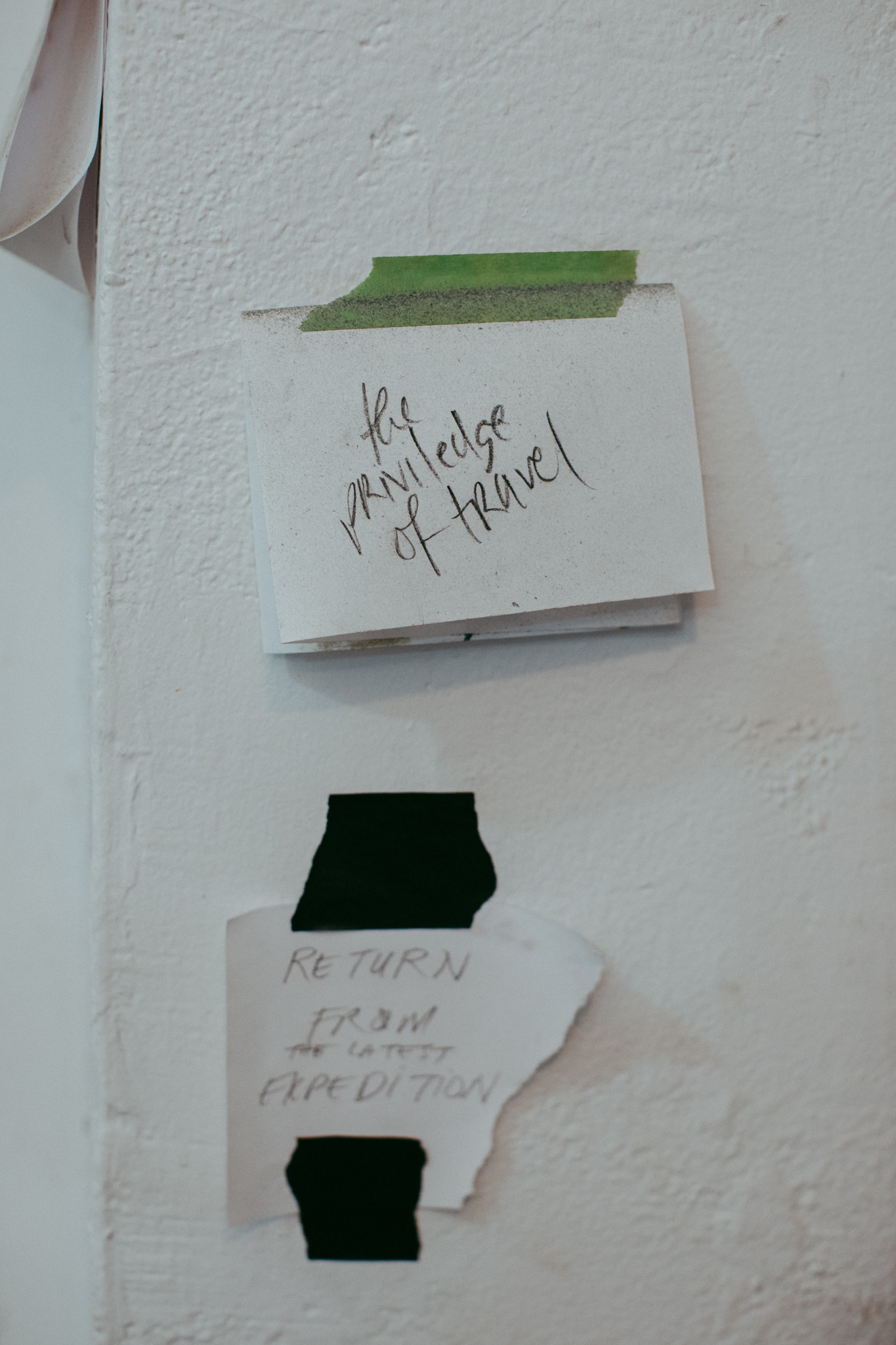

GAL: Is it important for certain pieces of your own making to have wall text? Or do you prefer them to remain untitled and have no written cues?

TOO: The best advice I ever got was in graduate school from my professor, Tvat. All my drawings at that point were untitled. I'm just going to say it—I was lazy. I didn't want to frame the work properly because I was afraid I didn't know how. She sat me down after a critique and told me, “Do not leave your work at the mercy of the viewer. You need to be in control of the framing. You can be ambiguous just enough, but give them a framework. Once you leave it untitled, it's done; with a title, the work can be so much more.”

She was trying to indicate to me how there's a conversation to be had between the title and the image, which can be so powerful. Someone might approach an image, and obviously won't know anything about it, but then they'll read the title and suddenly there’s another story there, there’s an in. And that, to me, is when the imagination starts to work. The title helps the viewer set the stage, you know?

GAL: Yeah, I agree.

TOO: Some artists feel really uncomfortable limiting their work with text. I can understand that. As an image maker, there needs to be a balance between text and image. For me, the problems arise when there’s an expectation about injecting text into every visual. For instance, how institutions or publications, generally, would never ask a writer to draw a picture about their novel or short story for the sake of explication. It makes no sense. And yet, an artist is consistently asked to write some essay or dissertation about a picture or work they created. I’m all for writing, but the treatment of visual language is far too disproportionate and misunderstood. I’m of two minds about it, but in the end, people need to understand: sometimes the reason for the picture is because the words aren’t sufficient.

GAL: It's not your job. It’s why authors hire illustrators and designers to create book covers.

TOO: Right. It can be a part of it, but completely separate—and it’s a choice, not a requirement. You want to find that balance and for me the title is the balance. The title is enough. In terms of what happened with TWD, there are a lot of players involved and many pieces that are rather complex. I didn't want to give the audience the fan-fic details of my work. They didn't need to know the family tree. They don't need to know all of that, but they need to know the framing. So, there’s a little letter that you see when you walk in that’s part of the conceit of the show. It states that I'm the deputy private secretary of this family, who are presenting their collection. As their representative, I'm sort of a communications liaison between the public and this family.

GAL: Oh my God, I love that so much.

TOO: This letter from me to the audience is the introduction. There are moments in it where the real and the imagined cross over. Lines of, “This grand family is one of the oldest and noblest clans of Nigeria. With family seats in Lagos and Port Harcourt.” And these are real places in Nigeria, real cities, but the “Amara Palace” in Onitsha and “Udoka House” in Lagos don't really exist. I think J.K. Rowling said in an interview once that the space where magic happens in a story is when you combine reality with fiction.

GAL: Yes! A combination functioning both as a gateway to a magical world and an anchor for common reference purposes.

TOO: When Harry goes through platform nine and three quarters. That's set at an actual train station—it’s a real place, and not a real place. The location has a double meaning, a duality. In my own way, that was what I was trying to get at with the framing of TWD.

GAL: What would you title your memoir and why?

TOO: Oh, man. There’s one title I could see happening: “Because It Applies.” Or, if I’m being coy, “Is This Story Necessary?” Which is a question I often ask myself before I begin any project or series. Or, before I click the “publish” button on any social media platform.

GAL: Who are your favorite authors?

TOO: Toni Morrison. Octavia Butler! And James Baldwin, always! And Zadie Smith—especially White Teeth and On Beauty. I'm also going to say, even though it's super cheesy, because she's like my little sister in a way: Yaa Gyasi. I read Homegoing and I was blown away by how perceptive and moving it was. The whole time I was reading it, I was squealing, “Oh, my gosh, my baby, Gyasi!” It's so good. I also really enjoyed reading Hal Borland's When the Legends Die in school. That's one of my favorite books. I’m obsessed with Takehiko Inoue’s Vagabond series. I can re-read those volumes over and over. Every single panel is a master work.

GAL: How often do you read?

TOO: Not enough. Living in New York, everyone knows the only time you have to read seems to be while riding the subway. I really wish I could read more. One of the things I miss most from growing up is you have the time to read. The luxury of sitting down for hours, to lose yourself in a book or anything that requires focus. You don’t realize how much that time affords you and what you absorb has a profound effect on how you process information and understand the world. As you get older, your time gets co-opted, it gets compromised, and you forget the power of thinking things over and taking your time before acting on anything. Reading also helps my work. I get a lot of ideas reading other stories—non-fiction and fiction. Just hearing and reading stories helps immensely. More often than not, I listen to a lot of audio books while I am working.

GAL: Tell us about your favorite audiobooks.

TOO: It's two-fold. When I work, I listen to a lot of podcasts and audio books. I love the “LeVar Burton Reads” podcast and long-form podcasts like BBC 4’s “A Point of View,” and radio dramas. With audiobooks, I recently listened to Call Me by Your Name, because I was interested in the film and wanted to read the story before seeing it in the theater. No shade on the movie, but the book is really excellent—because the form allows for more time to explore the interiority of the characters. The film is a visual medium entirely, with minimal dialogue, which I love as well. They are two completely different entities, which exist in parallel with one another. Both exploring that internal world and both are incredibly immersive, yet remain separate and contained in their own way. It’s one story in two ways, I guess.

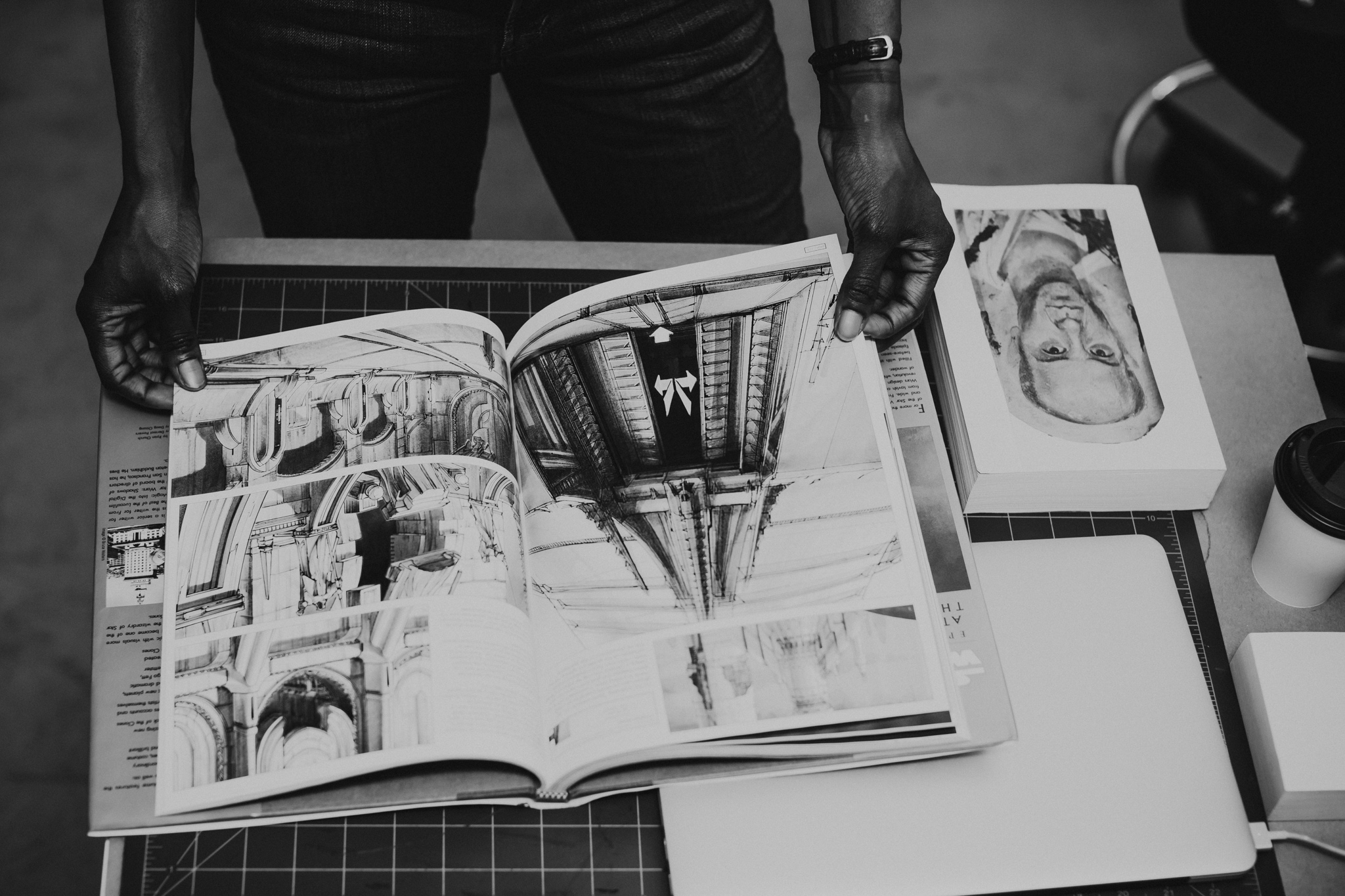

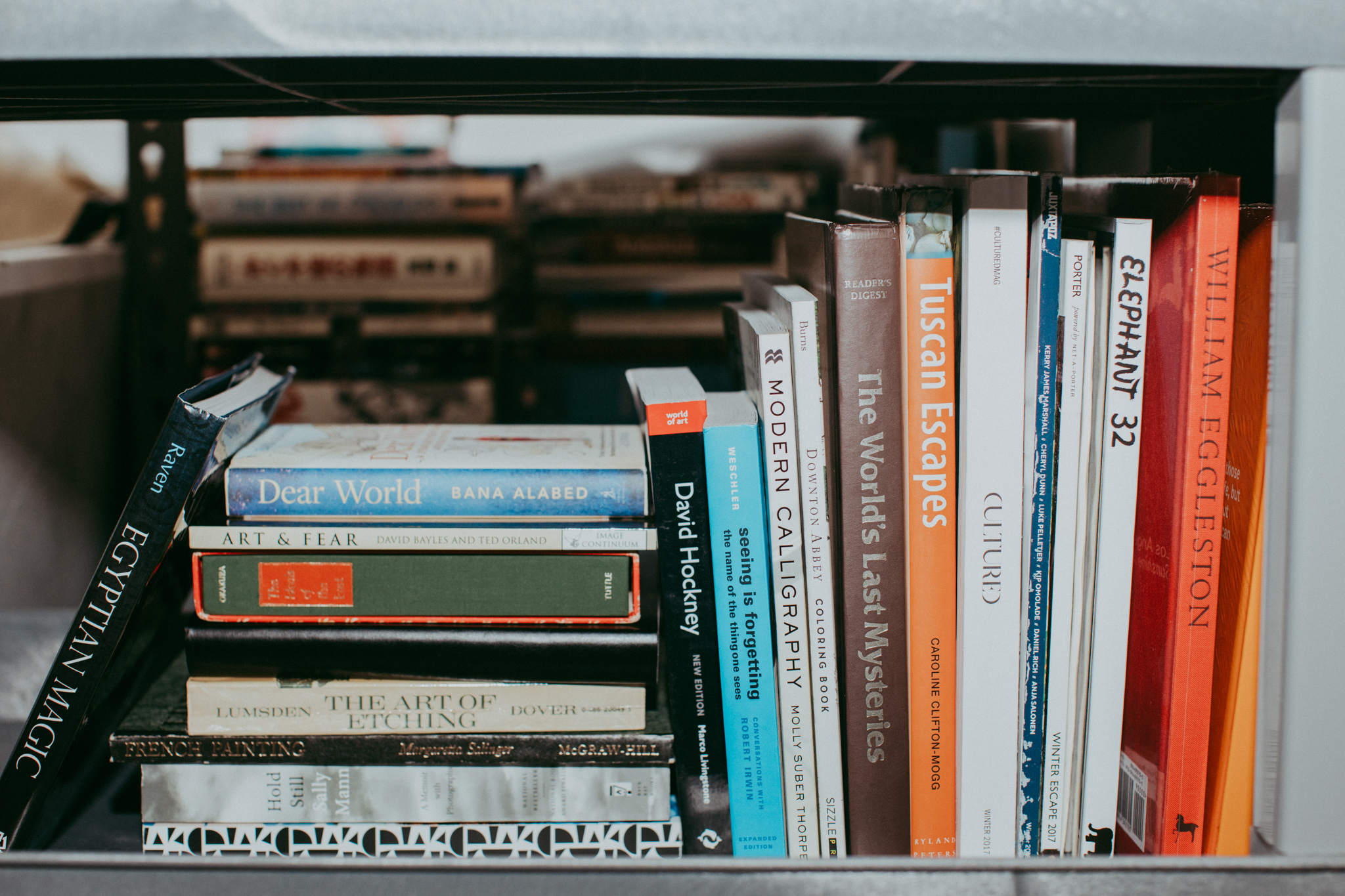

GAL: Similarly to how literature can sometimes intimidate, looking at art can be intimidating to people. Are there any books that you would recommend for reading about art and artists or engagement with process?

TOO: John Berger's Ways of Seeing is one of the most groundbreaking books about art ever written, I think. It’s also accessible to everyone. It's not just about artworks and art-making alone, it's about images. About the visual, and how we perceive the world through that. He really is trying to help people understand visual language and how things work and what they mean and why people make the decisions they make when they create a picture. Image making is an activity, which involves so many tools and choices, and he really breaks it down regarding power, dynamics, and positioning.

You know what? When he died, I cried. I never met this man, never heard him speak in person, but I cried. It was like we lost a treasure. We lost a person who was constantly engaging with a question, never settling. Like James Baldwin used to say, he “exposed the question the answer hides.” Whatever that question was, he went after it, chasing it, dissecting it like a surgeon.

His precision, his line of inquiry, is so inspiring. He just…goes in. All of my favorite authors do, but I love how he doesn't discount any flippant remark. His writing compels us to ask more questions: “Why would you make that statement? What does that mean? What is that about?” I love that. I really enjoy that kind of thinking.

It's the same with images: “Why would someone use blue there? Why would you put that person in that left-hand corner as opposed to the right?” There are choices people make that mean something, and when you start paying attention to them the world opens up, it becomes a lot more interesting. You become more cognizant of how power structures work, too. Certain things are positioned in certain ways for a reason.

GAL: Any others?

TOO: Art and Fear by David Bayles and Ted Orland. The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard is another great one. Anything written by Sophie Calle. It might seem out there, but she’s a great primer for people to think about the potentiality of the image and art-making.

GAL: Do you read any magazines about art?

TOO: Yes; however, some head into didactic, “art speak” territory from time to time, and I can’t help but think while reading them, “Girl, calm down.” It’s true, you will read some articles and it’s hard to curtail the urge to ask the author, “Do you actually understand what you're saying? Or are you just using big words for a count?” I mean, I know what those words mean, but you could easily have said that in a shorter, more concrete, and less vague paragraph. Frieze is a great magazine, at least it was back when I was in grad school. There were some Frieze issues which were immensely educational for me. I’d suggest starting there, maybe?